A Universal Language

Becomes bounded and personal – Meaningful…

The Language of My Puzzle Games

Almost everyone, all around the world, has played a puzzle game of some sort at least once in their lifetime. It is something people of all ages could participate in because there is such a wide variety of them. I always thought puzzle games like word searches or sudoku were simple and easy to understand. A simple activity that did not have much depth to it, but I was wrong. Upon gathering information for this essay, I realized how much language, culture, and social bonds are involved in these activities. How a whole new language can emerge from some puzzle games that only you and another would understand, or maybe even a whole group of people. However, when I was younger I did not really appreciate this unnoticed beauty of puzzle games, or I did not yet understand that language could be found in just about anything. My mother would always tell me to appreciate the small beauties in life, because everything holds meaning. I would just agree and say, “Sí Mami,” but I never thought that puzzle games would affect my life so much, as well as my understanding of literacy and language as a whole.

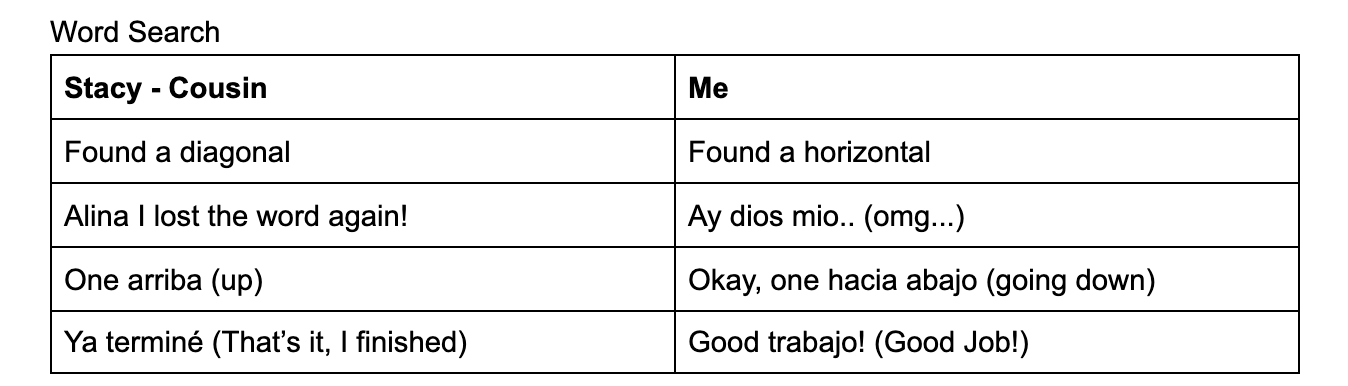

Word SearchThe very first puzzle game I remember playing was word search. I enjoyed solving those puzzles like a caterpillar emerging from its cocoon, releasing a beautiful butterfly. It was freeing and comforting for me. A way to escape the overwhelming loudness of city life growing up. My older cousin, Stacy, introduced it to me when I was about 6-7 years old. I had seen her completing one and thought it looked interesting, so I asked if I could help. She explained the rules to me, “You have to look for the words listed on the bottom. They can be found in any direction including horizontal, vertical, diagonal, left, right, up, and down.” After that, I asked her to complete a word search puzzle with me every day after school. We even started creating our own “code language” for the direction we found the words in. “One arriba” meant one up (word going in an upward direction) and “One abajo” meant one down (word going in a downward direction). Then we just used “one diagonal, horizontal, and vertical” for words we found going in those directions. What was interesting is that neither of us were fluent in spanish. In my household we use a lot of “spanglish” or as others would say, “broken english.” It is what we grew up hearing, so it made sense to us. Hearing “one arriba” was not as foreign to me as it would be to a stranger who does not understand our word search Spanglish language. We were fluent in that language and through it my cousin and I grew a stronger bond. We could easily switch from our Spanglish code to a random topic while completing a puzzle, and people who did not understand looked at us with a face of awe mixed with a dash of confusion. Even today, we know that when we sit down together and complete a word search, we are both completely literate in our word search Spanglish language, and that brings me a warm sense of comfort.

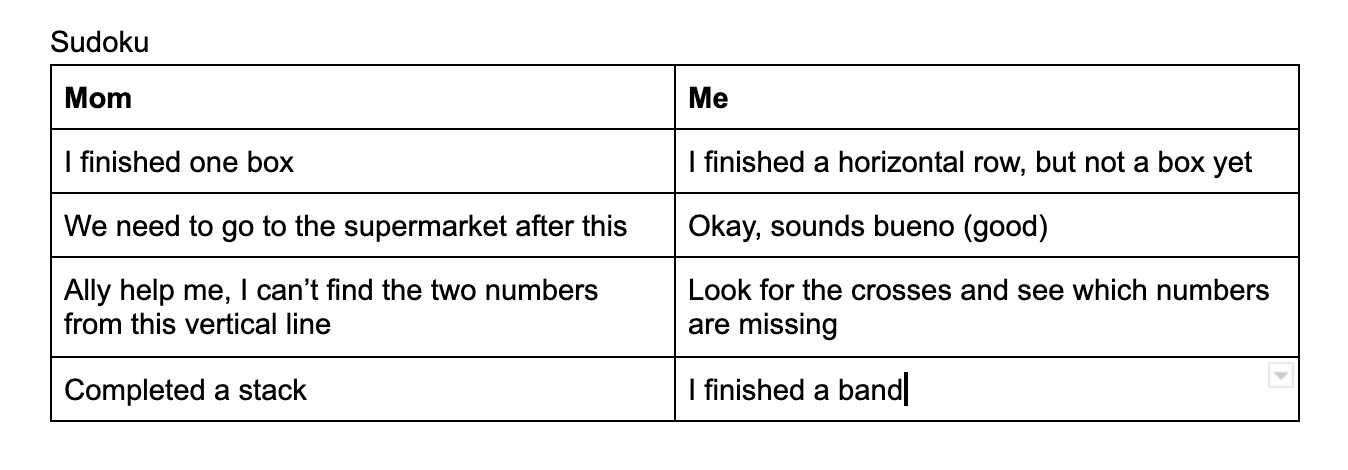

SudokuOn a more humorous note, is the second puzzle game I was introduced to growing up, Sudoku. I say it is humorous because there are many laughable situations surrounding this game for me, despite its seemingly boring appearance. My mother was the first person to introduce sudoku to me. She had originally started playing it on the train to work as a way to kill time, and when she finished she kept it in her black worn out purse untill she got home. As many other curious kids would, I scavenged her purse for candy since she would sometimes bring some home from her job. However, instead of a mouthwatering bag of tropical skittles, I found a book full of strangely placed numbers in little boxes, inside of bigger boxes. It was confusing, yet intriguing, so I asked my mother if she could explain what it was to me. Thinking it would be simple I listened to my mother, “There are 9 boxes that contain numbers from 1-9. Some numbers are missing from each box, which is what you must fill in. The catch is that each row going horizontally and vertically has to also contain the numbers 1-9 and cannot repeat any one number.” The words began to go in one ear and out the other, like the powder sugar that would flow through the sifter when my mother and I baked. That’s what I started thinking about when I could not understand what she was saying, baking, candy, toys, tv, a different and seemingly simpler puzzle game. Nonetheless, I still wanted to learn because my mother would write those numbers on the grids quite gracefully, making it look easy. Little by little, I started to pick up on the patterns in the game. How to look through each row and box to find any missing numbers and to check that no number has been repeated. How to guess where a number would most likely end up based on the placement of other numbers. I had become fluent in the formal language of sudoku, so much so that when I introduced it to my little brother, we made up our own special code for the game. The big boxes were called burgers and the tiny boxes that contained each number were called seeds. We started this after having cheese burgers for dinner and then playing sudoku, jokingly calling the boxes burgers, but it stood. It is two small phrases that seem extremely silly but when I ask my brother, “Hey, want to play burgers and seeds?”, he answers instantly knowing exactly what I am referring to. Sure we know the correct terminology of the game, but it is our special sudoku code language that makes it that much more memorable and meaningful.

Dominoes

Growing up I played many different kinds of puzzle games that I still play today, but the most memorable and significant game is Dominoes. Being part of a Dominican household, Dominoes were played at every family gathering and it caused quite the commotion. I enjoyed watching my uncle Tony shout, “Trancado!” while laughing at my annoyed family members. Though I did not know what it meant at the time, I thought it was exciting to watch how all my older family members were able to play the game with so much ease. It seemed like they were just placing the tiles down intuitively and running with it. However, I came to learn that Dominoes was much more complicated than I thought when I began playing with my father and grandpa.

It was at my grandpa's tiny apartment, on a small foldable table, that I began learning the language of Dominoes. I watched as my grandpa and father would place the tiles down strategically and look at each play with an analyzing expression. It was so different from when my rowdy uncles would play at family gatherings. My father and grandpa only spoke Spanish to each other since my grandpa knew little to no English, and it is also my fathers mother tongue. I am not fluent in Spanish, so I was not really able to verbally communicate with my grandpa except for simple phrases and words. It was not until he asked me, “Quieres jugar un mano?”(Do you want to play a game?), that I was able to understand a different language, one we could both communicate through. We began the game, each with five dominoes. My grandpa pointed to one domino tile and simply said, “una ficha,” (one tile) and I repeated after him, like a toddler learning a new language for the first time. My father began explaining the rules, “Each ficha has a certain number of black dots on its surface, which is divided on the tile, except for los blancos (the blanks) that have no black dots. You have to place the matching amount of dots with the same amount of dots on the previously placed ficha.” He stopped there and I was able to understand the way the game was played on a basic level.

After playing for a while my grandpa suddenly says, “Capicú!”. My father begins to chuckle and I stare at them in confusion waiting for an explanation. He says, “Él ganó (he won)”, and explains that Capicú means you win the game with both end tiles having the same amount of black dots on them. I retained that information quickly and asked them to teach me more. There were terms like Chucha (double blank title), Trancado (blocked game), Chuchazo (winning the game with a double blank), and many more. I made it a goal of mine to learn all of these terms and rules, so that next time we played I would be able to properly understand. So, every time I went to visit my grandpa's house we played a game of dominoes and after a few visits, I became fluent in the language of Dominoes. A language so close to me because it represents not only my culture, but also the way I was able to communicate with my grandpa. When we played Dominoes, there was no miscommunication or confusion, but instead each word and phrase flowed smoothly through our lips as we spoke of fechas, trancados, and Capicús. The memory of playing dominoes with my grandpa will always stay with me as a small beauty (as my mother would say), and the language of dominoes is one I intend to pass on to many generations ahead of me.